Why the World is Turning to Cash

With an ever-increasing range of digital payments available, it may come as a surprise that demand for physical money—especially high-denomination notes—is also rising, but it shouldn’t. The comfort and security offered by cash in a crisis are as tangible as ever, and in a digital world, the privacy of cash transactions is a unique commodity.

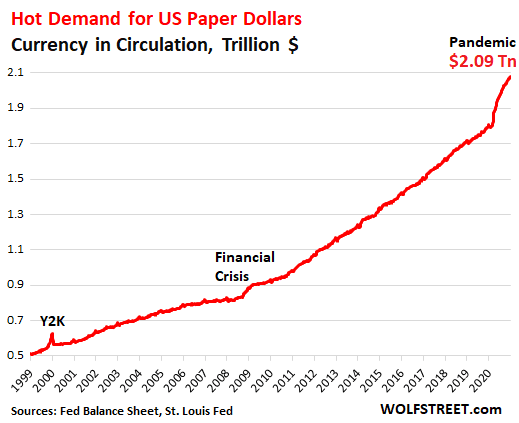

In America, and other countries using its currency, demand for dollar bills has been setting new records, reaching $2.09 trillion by the end of 2020. Having risen 16 percent since February that year (pre-pandemic) the figure has also doubled since 2011. So, while COVID-19 has driven a normal surge in cash holdings—with periods of uncertainty typically seeing a rise of currency in circulation as people turn to the dependable security of cash—the upward trend predates the pandemic, which has only accelerated it.

High-denomination notes are especially in demand, with the volume of $100 bills outstripping that of $1 bills in 2017 and continuing to accelerate ever since.

When interest rates are low, the opportunity cost of holding currency instead of putting money in the bank is lower, and people may tend to hold more currency.

Across the pond in the UK, Bloomberg says there’s evidence that increasing numbers of people are ‘storing their wealth under the proverbial mattress.’ With interest rates on savings accounts the lowest on record and central bank officials emphasising the possibility that negative interest rates could be introduced—meaning people would have to pay banks to hold their money—it’s easy to see why Brits are turning to cash.

Switzerland, with the lowest official monetary policy rate in the world, is already at sub-zero interest rates (-0.75 percent). This means depositors must confront the prospect of being charged by their bank for keeping money in a savings account, which is driving a rise in people electing to store it in the form of cash.

Euro notes in circulation are continuously increasing, with an average annual growth of five percent over the past ten years, according to a recent European Central Bank report. The same report notes that ‘euro cash flows are mainly driven by local-specific determinants’ such as economic activity, foreign tourism and inflation, rather than external factors like global uncertainty—as in 2020—or short-term interest rates in the euro area.

The high proportion of large denominations [being hoarded] indicates that banknotes are used not only as a means of payment but also—to a considerable degree—as a store of value. The persistently low level of interest rates is a major factor in the rise in demand for banknotes.

Japan is seeing bumper demand for its highest-value note. By the end of 2020, the number of 10,000-yen notes in circulation was up 5.3 percent from 2019, when the typical year-on-year increase is two to four percent. The country’s highest-value coin (500 yen) is also more in demand, up 3.9 percent at the end of 2020 compared to 2019.

In addition to financial motivations, physical money is a safeguard in cases where it could be needed as an emergency form of payment. British supermarkets hit by card payment outages in late January had to ask people to pay in cash. This—in the midst of the pandemic—serves as a reminder that there are innumerable scenarios involving internet or power outages in which cash would be the only way to pay for essential items.